Selborne Scheme

The Selborne Scheme (also known as the Selborne-Fisher Scheme) was introduced in 1903 whereby the Royal Navy consolidated initial entry and training for officers of the Military Branch, Engineer Branch and Royal Marine Forces into one Common Entry (by which name the scheme was also known). The scheme was named for the First Lord of the Admiralty of the day, the Earl of Selborne, although the driving force behind the scheme was the Second Sea Lord, Admiral Sir John A. Fisher.

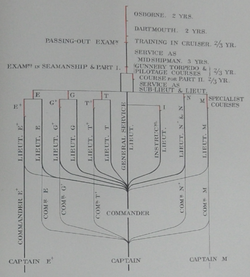

Boys entered as Naval Cadets between the age of 12 and 13 studied for two years at the Royal Naval College, Osborne, two years at Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, and a period in a training cruiser at sea before joining the Fleet as Midshipmen. After three to two years' sea service the teenagers could then qualify for the rank of Acting Sub-Lieutenant, confirmed after passing all examinations for the rank of Lieutenant. As Lieutenants they could then specialise in gunnery (G), torpedo (T) and navigating (N) duties as normal (and eventually signalling (S) duties). The Selborne Scheme introduced the specialisation of engineering (E) would have created that of military (M), i.e. Marine.

As envisaged the officers of the various specialisations were meant to be interchangeable, and allowed to revert to general duties by the rank of Captain. However, it was planned that engineering officers could elect to specialise further as (E†) and remain specialists for the remainder of their career, or Commanders (M) could remain in marine line and be promoted to Captain (M).

The last separate entry for the Royal Marines was made in June, 1907, but was reintroduced in 1911. When the first of the New Scheme began to specialise in 1913 two Sub-Lieutenants volunteered for service with the Marines but became Probationary Lieutenants, Royal Marines, rather than Sub-Lieutenants (M).

In 1922 selection for engineering specialisation was introduced at the rating of Midshipman, at which point those selected went to the Royal Naval College, Keyham for four years' study. In 1925 engineering again became a separate branch with purple distinction braid between the stripes. (E) officers were compelled to revert to the executive branch or remain.

Background

Selborne told the House of Lords in 1926:

The scheme of 1902 is generally known as the Selborne-Fisher scheme, but it would be much more correct to call it the Selborne-Kerr-Fisher scheme, because Admiral of the Fleet Lord Walter Kerr, who I am glad to say is still with us to-day, was the First Sea Lord. Lord Fisher was Second Sea Lord. Lord Walter Kerr was an officer of the old school who never would dream of agreeing to a change on mere grounds of theory. He would never agree unless he thought an important change was essential to the good of the Service. I think a great deal too much stress has been laid on Lord Fisher's name in this matter. Lord Walter Kerr was just as responsible for the scheme as Lord Fisher, but Lord Fisher, as the Second Sea Lord, was the particular member of the Board of Admiralty who had the work of administering the scheme. Under that scheme there was to be a common entry for all the officers of the Navy, and they were to specialise when they reached the rank of Lieutenant, and decide whether they would become engineer officers or not.[2]

Main Features

In his memorandum of 16 December, 1902, the First Lord of the Admiralty, the Earl of Selborne announced:

It has been decided henceforth—

1. All Officers for the Executive and Engineer branches of the Navy and for the Royal Marines shall enter the Service as Naval Cadets under exactly the same conditions between the ages of 12 and 13;

2. That these Cadets shall be trained on exactly the same system until they shall have passed for the rank of Sub-Lieutenant between the ages of 19 and 20;

3. That at about the age of 20 these Sub-Lieutenants shall be distributed between the three branches of the Service which are essential to the fighting efficiency of the Fleet—the Executive, the Engineer, and the Marine.[3]

Ages of Entry

In the first entry in September, 1903, the limits of age were 12 to 13. The reason given by Selborne was that:

the age of 12 to 13 not only corresponds to that at which the history of the Navy shows that boys have been most successfully moulded to sea character, but also it corresponds to the age at which boys leave Private Schools and, therefore, to a natural period in the system of education which obtains in this country.[4]

For the next entry, January, 1904, the lower limit of age was raised to 12 years and four months.[5] In 1906 the lower limit was raised by another four months to 12 years eight months.[6] The Custance Committee in its third report of September, 1912, specifically advised against raising the lower limit any further.[7] However, in November, 1913, the lower and upper limits were narrowed to 13 years four months and 13 years eight months respectively, taking effect in January, 1914.[8]

Nomination and Appointment

"Appointments to Naval Cadetships will be made by nomination subject to the nominees passing a qualifying examination. Candidates who fail to pass will not be allowed a second trial."[9]

Baddeley claimed before the Custance Committee that "The word 'Nomination' no longer exists. That is abolished."[10] The term was still in use then, however. It was not until the end of 1913 that the regulations were amended:

No nomination is required by a Candidate for a Naval Cadetship. All that is necessary is to send an application to the Assistant Private Secretary to the First Lord of the Admiralty.[11]

Interview

All candidates except Colonial Candidates had "to present himself before a Committee, which will interview each applicant separately". Nominations were then given by the First Lord to the candidates recommended by the committee. A committee was usually presided over by a flag officer and comprised a second naval officer, an educator such as the head master of a public school, and a member of the First Lord's Private Office.

From the first committee in June 1903 the candidates were given "ten minutes' writing on an easy subject", according to J. Alfred Ewing.[12] Fisher put it this way:

each of them appeared separately before the Committee with a short written statement (for which he was allowed about ten minutes) on some popular subject. Alternative subjects were offered in each case. This tested the handwriting, spelling, and general knowledge of the candidate and his power of expressing himself tersely.

As an instance, one little boy of 11¾ years of age was asked to state what he thought were the chief duties of a Naval Officer. He replied:—

- "First, to serve his King and Country.

- "Second, to be the last person to leave his ship, if wrecked.

- "Third, to obey his superior officer."

The subjects for the written statement were frequently changed—always twice a day and sometimes oftener, and it is considered to have been impossible under the procedure adopted for the candidate to have had any inkling of the subject of the written statement or of the Examiners' questions.[13]

Captain Trevylyan D. W. Napier, who served on the second committee in November, suggested the Spanish Armada and "Difference between Ancient & Modern Ships, with rough drawing" as subjects for the statement.[14] He suggested to Baddeley that reading a page of a book or a newspaper paragraph might be substituted for the writing, so that the candidate could then explain what he had read to the committee.[15] Instead, for the second committee "the boys were also this time to read through a short story of poetry for five minutes before the interview. The power of telling in their own words the tory they had read proved a valuable test of the boys' intelligence and mental grip".[16] By the time of the sixth committee in February 1905 the candidates were "drafted—three at a time—into a separate room where they are given a "10 minutes essay" on some easy subject, and if time permits a short piece of prose or poetry to read through".[17]

The candidates then went in, one at a time, for their interview. Baddeley implied that the length of each interview was around ten minutes in June 1903 ("it is hard enough to keep a fair standard in assessing a boy when one's whole attention is devoted to him for 10 minutes"),[18] and by the time the sixth committee reported in February 1905 he stated that each boy had "an interview of from 10 to 15 minutes".[19] By the beginning of 1914, according to an official Admiralty guide, "Each candidate is interviewed for about 15 or 20 minutes."[20]

Baddeley lamented to Napier on 19 October 1903:

Hyde Parker is quite right, new methods are I think quite desirable - the new committee has an entirely free hand as to its procedure; in fact I was rather disappointed that there was so little hint of originality at our meeting the other day. I was necessarily the exponent of the previous plan, but quite hoped that new views would turn up!

For that reason I rather regret having shown specimens of previous questions, but trust that the new committee will take them as a warning than as a guide.[21]

Davies claims that "The 170 candidates interviewed in 1903 were seen in seven working days, at an average rate of about 24 a day."[22] However, according to the printed reports the first committee interviewed 279 candidates in 11 days, and the second committee 151 in eight, or a total of 430 in 19 days.[23] This translates to 25.36 a day for the first and 18.875 for the second. Baddeley stated that the second committee "was able to conclude its labours in eight days, including two days of only three hours' session".[24]

Napier appears to have been paid for 13 days of committee service.[25]

Lord Blackett went for interview in the Summer of 1910. He recalled:

The method of entry at that time was not only a written examination but also an interview, by a board of four admirals. There were many tales of these ordeals and of the unexpected questions which might be shot at one, such as, "What was the number of your taxi?" or some other test of the applicant's memory. Luckily for me the first question I was asked was what did I know about Charles Rolls's flying machine, in which he had made the first double crossing of the Channel the day before my interview. I was an aeroplane enthusiast and proceeded to bore the admirals by telling them more than they wanted to know about Rolls and his machine.[26]

Even a Nobel Laureate can make mistakes, as it Blackett could not have been examined by "four admirals". The chair of the committee would have been Admiral Sir Reginald G. F. Henderson.[27] Rolls' flights took place on 2 June 1910, which dates Blackett's interview to Friday 3 June (if his memory is correct).[28]

Some of the questions could be construed as little better than bluff. S. Brian de Courcy-Ireland recalled of his 1912 interview, "I remember being asked 'How many arches there were to Bideford Bridge?' And I caused a great deal of amusement because I was very surprised they didn't know!" Later, "They asked me why I always talked in a sing song voice and that rather upset me."[29] Eric W. Bush, who also entered the Navy in 1912, wrote:

On arrival at the Admiralty, I was put in a room with another candidate. We never spoke. This behaviour is so typical of boys that comment seems unnecessary. Anyway, I never saw him again.

To keep my mind occupied while waiting, I was given an essay to write. As I struggled through it, a chap came into the room. He did not seem to have anything to do with the interview, but I stood up politely and answered his questions. I think he must have been a naval officer or something of the sort, because he gave me the impression that he had just left the Navy and felt sad about it, although he did not actually say so. He was still talking to me when the Admiralty Messenger came in and said that the Board was ready.

I was taken across a passage and shown into a room which, I remember, had two large windows looking out on to a courtyard. At a table in the centre sat my inquisitors. Two were naval officers, one the headmaster of a public school and one headmaster of a private school. The fifth was a Civil Servant.

The Admiral greeted me and told me to sit down at the table. I was first asked a few questions in Latin translation and managed them all right. Then the Admiral inquired why I wanted to join the Navy. I had the answer pat. Was I keen? "Yes." Mad keen? "Yes, rather." What would I do if I failed? "Try again, of course."

He then wanted to know if I had any relations in the Navy. Did I like games? Finally, I was asked to point out some places on a map. Oh dear, I could not find Tasmania or Madagascar. What was I to do?

When the interview was over, I stood up, made a little bow, and turned to leave the room. Over near the doorway I tripped over an electric light lead.[30]

Stephen W. Roskill, who entered the Navy in 1917, wrote in his memoirs:

Apparently I got through my medical examination easily, & we then moved to the Union Club in Cockspur Street, for the interview. I was first told to write an essay on "Methods of Economy in War Time", but have no recollection of what I said. After I had handed it in an elderly man, who must surely have been a naval pensioner, took friendly charge of me, brushed my hair & adjusted my tie & conducted me to the interview room, where I was bidden to take a seat at a table facing five or six gentlemen all in plain clothes. I learned later that the chairman was Admiral Sir George Patey. The Board apparently asked me a lot of questions, among them the capital of Uruguay (or Paraguay) - which I got wrong. When however I was told to read & translate a passage in French they were apparently impressed by my fluency in that language, which I owed chiefly to my mother; but when I was asked to repeat some lines from Ovid's poetry my mind went absolutely blank, & I felt myself blushing to the roots of my hair. I now think that attack of amnesia may have acted in my favour, as the Board was surely not seeking candidates with advanced knowledge of the ancient classics.[31]

Roskill's opinion of the importance of the classics is perhaps at variance with Bush's experience. He also once wrote to another naval officer, "Please don't rely on quotations from memoirs or autobiography"![32]

Grading

A system of grading was utilised by the first five committees:[33]

| Category. | Classification. |

|---|---|

| Fit. | α+, α, α- |

| Doubtful, though promising. | β+, β, β- |

| Unsuitable. | γ |

Lord Helmsley, the First Lord's political Private Secretary, thought that in some cases it was too difficult to classify some of the boys using + and - signs, and proposed five classifications A, B, C, D, E, where C represented the average.[34] However, according to Baddeley, on the sixth committee which sat in February, 1905: "The present Committee found that so far from having much difficulty in classifying the candidates, it could safely subdivide the large middle or β Class still further".[35] This resulted in the following classification of that committee's results:[36]

| α+ | 2 | good β+ | 5 | good β | 25 | β- | 19 |

| α | 8 | β+ | 28 | β | 38 | γ | 19 |

| α- | 13 | poor β+ | 7 | poor β | 6 |

Qualifying Examination

In the original memorandum it was stated:

The entrance examination for the Royal Naval College, commonly known as the "Britannia" examination, will be of an elementary kind, and confined to those subjects in which a carefully-educated boy has usually been instructed up to the age of 13. No change will be made in the present system of entering boys for the competition, but the medical advice is conclusive that at this early age the examination must not be severe, and indeed that no examination of boys at this age or at the later age now obtaining can be considered an accurate test of what their comparative faculties will be when they have attained manhood.[37]

The qualifying examination as established comprised six subjects:

(1.) English—(including writing from dictation, simple composition and reproduction of the gist of a short passage twice read aloud to the Candidates.)

(2.) History and Geography, with special reference to the British Empire.

(3.) Arithmetic and Algebra (to Simple Equations).

N.B.—Two-thirds of this paper will be in arithmetic.

(4.) Geometry (to include the subject matter of the First Book of Euclid, or its equivalent, with simple Mensuration. The use of instruments is allowed.

(5.) French or German, with an oral examination, to which importance will be attached.

(6.) Latin (easy passages for translation from Latin into English and from English into Latin, and simple grammatical questions).[38]

Length of Training

In Selborne's 1902 memorandum it was envisaged that "Cadets will remain under instruction at the Royal Naval College for four years before going to sea".[39]

In response to the mounting shortage of officers Churchill proposed to Jellicoe on 10 March, 1914, that an option for relief might be to "Reduce the classes [sic] at Osborne from six to five, and fill up by new entries."[40] At a Board meeting of 26 March "Increase of Cadet Colleges and accommodation of Cadets discussed. As a principle Colleges to be organised on scheme of five terms at Osborne and six at Dartmouth."[41]

Specialisation

It was made clear at the start that officers might have to join a branch they did not want:

No nominations will be given to boys whose parents or guardians do not declare for them that they are prepared to enter any one of the three branches of the Service at the termination of their probationary period of service afloat.

As far as possible each Officer will be allowed to choose which Branch or Service he will join, but this must be subject to the proviso that all alike are satisfactorily filled.[42]

Progress

In May 1908 the first cadets entered under the scheme passed from the training cruiser into the Fleet as Midshipmen.[43] In May 1911 the first examination for the rank of Lieutenant under the new scheme took place at Portsmouth.[44] The first three to be promoted to that rank were Oliver Bevir, Kenneth Edwards, and James R. B. Kennedy, who were promoted on 15 February 1912.[45][46]

Executive

The first officer from Osborne promoted to the rank of Captain was Harold T. C. Walker on 31 December, 1931.[47][48]

Engineers

The first 17 officers selected to specialise in engineering were appointed to the Royal Naval College, Greenwich, on 1 October, 1913.[49] The first promotions to the rank of Captain (E) occurred on 30 June, 1936, with the promotion of John B. Sidgwick and Denys C. Ford, who had entered Osborne in January, 1904, and September, 1903, respectively.[50]

End of the Scheme

The last entry of officers for the Royal Marines under the old scheme took place in June, 1907. In 1911 it was decided to restart separate entries, with 11 joining in January, 1912 as Probationary Second Lieutenants, Royal Marines. In 1912 two Sub-Lieutenants volunteered for marine duties and joined the Royal Naval College, Greenwich as Probationary Lieutenants, Royal Marines, and not as Sub-Lieutenants (M). Charles H. Congdon retired as a Lieutenant-Colonel and Robert G. Sturges was knighted and reached the rank of Lieutenant-General. These were the only two Selborne Scheme entrants to ever join the Marines.

Reactions

Captain Rosslyn Wemyss of Osborne noted in a 1905 letter to Fisher:

[A] tendency on the part of the parents of some of the cadets at Osborne to hope at least that their sons might never become Lieutenants (E), with no chance of commanding ships or fleets, and I have a suspicion that, that for this reason, they have in some cases even discouraged their sons in their engineering studies.[51]

Speaking before the Douglas Committee in 1906, Admiral Sir Lewis A. Beaumont, Commander-in-Chief, Plymouth, opined:

The fundamental change which has been brought about by the common entry has already disturbed the Service in a great measure, and, speaking for myself, I do not think that it has the good will of the Service generally. I do not mean the common entry alone, but what follows from common entry.[52]

In their minority report on the Douglas Committee, Rear-Admiral Login, Commodore Briggs and Captain Bacon, in opposing the inclusion of the Engineer Branch in the Military Branch, made direct reference to the Selborne Scheme reforms:

As officers in touch with the sea-going Fleets, we would also remind their Lordships that the great changes which have taken place in the Navy during the past two years have created a great feeling of unrest and uncertainty which only loyalty has in a measure recently soothed. It is very undesirable, therefore, to introduce at the present moment any further important changes which are not absolutely necessary.[53]

Rear-Admiral Hugh Evan-Thomas, Captain of Dartmouth, whilst adamantly against change, believed that in order to give boys an extra eight months at school the age of entry could be increased to 13 years and six months, and the number of terms reduced from 12 to ten: five at Osborne and five at Dartmouth.

Class

By 1906 at the latest it was already known that the scheme was too selective. An anonymous Admiralty paper entitled State Education in the Navy, printed in March, reckoned that in the United Kingdom there were only 300,000 households with an annual income of £700 or more which could afford the £120 a year needed keep a son in the Navy from the ages of 12 to 20. This out of a total population of 43,000,000! "Surely we are drawing our Nelsons from much too narrow a class." It admitted that the scheme had ended the old Engineer entry where "many engineer cadets were of quite humble extraction, but even this outlet or safety valve for democratic sentiment is now finally closed".[54]

There seems to be only one way of solving this problem. Initial fitness must be secured, as at present, by careful selection at the outset, and if the promise is not fulfilled as time goes on—if brains, character, or manners prove wanting—ruthless exclusion, whether of duke's son or of cook's son, must be the inflexible rule. But do not exclude for poverty alone, either at the outset or afterwards. Let every fit boy have his chance, irrespective of the depth of his parents' purse. This might, of course, be done by a liberal system of reduced fees for cadets, midshipmen, and sub-lieutenants whose parents were in poor circumstances. But in the first place there would be a certain element of invidiousness in the selection of the recipients of the national bounty, and, in the second, mischievous class distinctions would inevitably arise among the cadets themselves—between those who were supported wholly or partially by the State and those who were not. It is most essential that there should be no such distinctions—that the cadets should be taught to look up only to those who are eminent in brains, character, and manners, and to look down only on those who are idle, vicious, vulgar, or incorrigibly stupid. Now, a common maintenance by the State would put there all on a common level of equality. Though the additional cost to the State would doubtless be great, the result would be well worth the extra expenditure.[55]

The Director of Naval Intelligence, Charles L. Ottley, wrote to Fisher:

Whether we like or not, this reform will have to come; sooner or later. Personally I believe that nothing but good would come from thus identifying the nation with Navy: and the great thing is to initiate the policy ourselves, from within the walls of the Admiralty: rather than from without.

There are of course two palpable difficulties in the way. One is the purely financial effect of the scheme. The country would be called on to bear the whole cost of the education of naval officers up to the rank of Sub Lieutenant. This will add perhaps half a million to the estimates.—

The other is the peculiar, but undeniable fact that the bluejacket does not relish being commanded by a man of his own class: but prefers an officer to be a "gentleman".—

The question as to what constitutes a "gentleman" is a very complex one. One thing alone is certain however. Money does not!

Nelson was a poor parson's son![56]

An April 1908 paper, Entry and Training of Officers of the Navy, admitted "Criticism has been directed against the expense of naval education under this system," but claimed that the fees only covered a third of the expenses incurred![57]

As regards the cost to the parents, it is stated that the fee of 75l. per annum practically excludes the children of poor parents from entering the Navy. It may at once be said that the Board of Admiralty would welcome a reduction of the present fee, or even its total extinction, so as to throw the Navy open to wider competition. But this is not a question for the Admiralty to decide, and is entirely a subject for the Government. As has previously been mentioned, the Navy Estimates already bear two-thirds of the cost of the education. From the point of view of the parents, the expenses of boys going into the executive line are no greater than they were before the new system was adopted. The boy who becomes an Engineer Officer under the new system certainly pays 75l. a year for four years, instead of 40l. a year for five years, and also requires assistance for three years more until he becomes a Sub-Lieutenant; but, on the other hand, he enters Osborne at 13 instead of Keyham at 15½, and his parents are thus saved the expense of his education and maintenance at home during those two and a half years, so that the net total increase of cost is not great. The same argument applies to the Marine Officer of the future, and instead of remaining at a public school, or a crammer's, until he is 18, he is taken at Osborne at 13; in his case there is decidedly a net saving to the parents. It cannot therefore be urged that the new system has in any way restricted the field of selection from a financial point of view, and if that field is considered too narrow the only alternative is a further reduction, or a total elimination, of the fees, the State itself bearing the increased cost.

It is probably unnecessary to reiterate the arguments for the present method of selection of candidates; the success of the system is its own justification. But it may again be pointed out that in place of a system of limited nomination the Board have substituted an open selection to which any candidate can present himself, with a subsequent qualifying educational test for those selected. If, however, the cost to the parents of the education—low as it is compared to that incurred in training for other professions—is still considered to withhold desirable candidates from coming forward, then it becomes a matter of State policy for the Government to decide; the Admiralty are quite prepared to reduce or abolish all fees.[58]

The average cost of a cadet at Osborne was calculated at £93 1s. in 1912.[59] With travelling expenses added it was believed the cost might rise to £110. It was again noted that "the cost of the colleges to the parents is at least 35l. per annum higher than that for engineers at the Royal Naval Engineering College under the old scheme.[60] The Custance Committee reported that "These expenses are reasonable as compared with those at the public schools", but pointed out that the schools were liberal with scholarships and also many boys did not board at them, both of which substantially lowered the cost to the parents. The Committee recommended lowering the fee to £24 a year for up to 20% of entrants at each examination, based on "the pecuniary circumstances of the candidates" and their passing the qualifying examination "with some credit".[61]

In September 1941 an extensive system of scholarships was introduced for up to 60 out of roughly 135 naval cadets entered at Dartmouth each year.[62] What the writer of 1906 called "a common maintenance by the State" had to wait until 1947 to be formally introduced. A new scheme of entry to Dartmouth at 16 was introduced, where "no fees or charges, either for tuition or board and lodging, will be payable".[63]

Historians have been attracted to the idea of class being examined in the interviews. Oliver Johnson has claimed that:

the more experience the interview panels gained, the more they would diverge from the script to gauge the background of the candidate, with questions including 'with what should one eat caper sauce, apple sauce or currant jelly', how to address a king, duchess or bishop and how much a piece of luggage cost to carry in a cab. Although well-intentioned, the scheme was quickly corrupted to preserve the privilege that the opponents of the scheme defended so vociferously.[64]

Johnson was citing text from Evan Davies's chapter in a volume on the scientist-sailor Lord Blackett, in which Davies wrote:

The committees did use techniques for judging candidates other than simply listing parental occupations. As the committees became more experienced, they moved a little from the script. It is fairly easy to see that asking a 12-year-old what was the lowest London cab fare or how much a piece of luggage cost to carry in a cab, or what sort of animals or birds would be regarded as game in this country, or with what he should eat caper sauce, apple sauce or currant jelly, or how he should address a duchess, a king or a bishop could establish social background. The connection between that last question and the relative performance of clergymen's and doctors' sons is pretty obvious. He was to be asked other questions that more directly addressed general knowledge, like 'What are the chief agricultural crops grown in England?' though the landed interest might benefit from that one, or 'What are the principal railways of England?'. There are some imperialist questions, like asking for names of eight of England’s colonies or six island colonies of the British Empire. Some are more directly naval: 'What is [sic] a lightship and a buoy and what are they used for?'[65]

The reference to moving "a little from the script" comes from Canon The Honourable Edward Lyttelton, Head Master of Haileybury (soon to become Head Master of Eton College), who wrote after the November 1904 committee, "I think we gradually learnt how to depend less on set questions and more on making the boys talk freely, in tempting them to with sufficient questions to see if they knew what they were saying."[66]

Davies also wrote:

Most children were simply not able to take advantage of the new system. Their parents lacked the financial resources to put them through the private educational system. Vincent Baddeley, for example, held that: "The Committee's business is to register its verdict on the general suitability of the boys, and social fitness is certainly on the 'counts'."

Baddeley, who wrote "social fitness is certain one of the counts", was clearly replying to a query from Napier, who had observed in his notes:

How far his social status by birth is to be considered I do not know, but altho generally speaking it is desired he shd be a gentleman yet it does not seem right that any class in a democratic country shd be rigidly excluded from serving their King & Country in the Navy if they want to whether it be on the Quarterdeck or Lower Deck.

Given that Davies was meant to be describing the conditions prevailing when Blackett entered the Navy in 1910, his decision to focus on questions from the first committee of June 1903, which were already discredited four months later, is curious. He claims "Clearly they were in use in the first set of interviews, as accounts of interviews make clear,"[67] yet cites only two examples in his endnotes (without actually quoting the questions posed): Louis H. K. Hamilton, who Davies admits was interviewed by the first committee, and Martyn B. Sherwood, who entered the Service in 1915 and was two years old when Baddeley sent the questions to Napier.[68]

Assessment

There can be no doubt that there was strong opposition to the Selborne scheme. However, what Marder termed "objections of a snobbish nature" aside, it is also clear that much opposition was based on incorrect and incomplete information regarding the scheme. It is all very well for Marder to damn "people who had not informed themselves as to the real nature of the Admiralty scheme",[69] but such a ridiculous attitudes ignores the fact that it was the Admiralty's responsibility to present the case for the Selborne Scheme not only to the public, but to the Navy itself. Evolution was inevitable in such an ambitious programme with a long gestation: From the announcement of the scheme in December 1902 it took until February—nearly a decade—before the first entrants under the scheme were promoted to Lieutenant.

Footnotes

- ↑ The New Scheme of Naval Training. Lecture by the Director of Naval Education. 11th May 1906. p. 23/

- ↑ Hansard. HL Deb 14 July 1926 vol 64 cc1075-76.

- ↑ Memorandum Dealing with the Entry, Training, and Employment of Officers and Men of the Royal Navy and of the Royal Marines. pp. 3-4.

- ↑ Memorandum Dealing with the Entry, Training, and Employment of Officers and Men of the Royal Navy and of the Royal Marines. p. 4.

- ↑ Report of the Director of Naval Education, for the Year 1904. p. 4.

- ↑ Report of the Director of Naval Education for the Year 1906. p. 4.

- ↑ Custance Committee. p. 23.

- ↑ The Navy List, Corrected to the 18th March, 1914. pp. 856-861.

- ↑ The Navy List, for October, 1904, Corrected to the 18th September, 1904. p. 879.

- ↑ Custance Committee. p. 168. Q. 4516x.

- ↑ The Navy List, for April, 1914, Corrected to the 18th March, 1914. p. 856.

- ↑ Selection of Candidates for Nomination as Naval Cadets. Cd. 1962. p. 3.

- ↑ Selection of Candidates for Nomination as Naval Cadets. Cd. 1962. p. 5.

- ↑ Napier papers. National Museum of the Royal Navy. RNM 2015/175/1-C. 53/89(6).

- ↑ Napier papers. National Museum of the Royal Navy. RNM 1989/53. Item 3.

- ↑ Selection of Candidates for Nomination as Naval Cadets. Cd. 1962. p. 12.

- ↑ Selection of Candidates for Nomination as Naval Cadets. Cd. 2450. p. 16.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Selection of Candidates for Nomination as Naval Cadets. Cd. 2450. p. 16.

- ↑ The Entry and Training of Naval Cadets. p. 9.

- ↑ Napier papers. National Museum of the Royal Navy. RNM 1989/53. Item 3.

- ↑ Davies. p. 26.

- ↑ Selection of Candidates for Nomination as Naval Cadets. Cd. 1962. p. 3.

- ↑ Ibid. p. 12.

- ↑ Return, for the Year ended 31st March 1904, of the Army and Navy Officers Permitted, Under Rule 2 of the Regulations drawn up under Section 6 of the "Superannuation Act, 1887," to hold Civil Employment of Profit under Public Departments. H.C. 319, 1904. pp. 40-41. Napier was paid £6 10s. for his committee work in October and November 1903. His contemporaries as junior Captains appear to have been paid 10s. per day for similar work, which translates to 13 days.

- ↑ Blackett. "Boy Blackett". pp. 1-2.

- ↑ Return, for the Year ended 31st March 1911, of the Army and Navy Officers Permitted, Under Rule 2 of the Regulations drawn up under Section 6 of the "Superannuation Act, 1887," to hold Civil Employment of Profit under Public Departments. pp. 36-37.

- ↑ "Cross-Channel Flight" (News). The Times. Friday, 3 June, 1910. Issue 39893, col A, p. 10.

- ↑ De Courcy-Ireland, Stanley Brian (Oral History). IWM 12243.

- ↑ Bush. Bless Our Ship. pp. 11-12.

- ↑ Roskill. A Sailor's Ditty Box. ff. 3-4. Roskill papers. Churchill Archives Centre. ROSK 24/3.

- ↑ Roskill to Desmond Dreyer, letter of 19 December 1981. Roskill Papers. Churchill Archives Centre. ROSK 7/239 Part 1.

- ↑ Selection of Candidates for Nomination as Naval Cadets: Reports of Members of the Interview Committees. p. 5. Selection of Candidates for Nomination as Naval Cadets: Further Reports of Members of the Interview Committees. p. 12.

- ↑ Selection of Candidates for Nomination as Naval Cadets. Cd. 2450. p. 12.

- ↑ Selection of Candidates for Nomination as Naval Cadets: Further Reports of Members of the Interview Committees. p. 17.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Memorandum Dealing with the Entry, Training, and Employment of Officers and Men of the Royal Navy and of the Royal Marines. p. 4.

- ↑ The Navy List, for October, 1904, Corrected to the 18th September, 1904. p. 879.

- ↑ Memorandum Dealing with the Entry, Training, and Employment of Officers and Men of the Royal Navy and of the Royal Marines. p. 4.

- ↑ First Lord's Minutes. Volume II. Dec. 1913 to May 1915. p. 35.

- ↑ "Board Minutes. Thursday, 26 March 1914." The National Archives. ADM 167/48.

- ↑ The Navy List, for October, 1904, Corrected to the 18th September, 1904. p. 879.

- ↑ Custance Committee. p. 24.

- ↑ Custance Committee. p. 27.

- ↑ "The Victoria and Albert off Yarmouth" (News). The Times. Wednesday, 8 May, 1912. Issue 39893, col A, p. 8.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 28581. p. 1173. 16 February, 1912.

- ↑ "Royal Navy" (Official Appointments and Notices). The Times. Friday, 1 January, 1932. Issue 46019, col B, p. 16.

- ↑ "Royal Navy" (Official Appointments and Notices). The Times. Thursday, 14 January, 1932. Issue 46030, col G, p. 6.

- ↑ "Royal Navy" (Official Appointments and Notices). The Times. Friday, 18 August, 1933. Issue 46526, col F, p. 5.

- ↑ "Royal Navy" (Official Appointments and Notices). The Times. Thursday, 2 July, 1936. Issue 47416, col F, p. 25.

- ↑ Quoted in Marder. I. p. 47.

- ↑ Douglas Committee. p. 127.

- ↑ Douglas Committee Report. pp. 43-44.

- ↑ State Education in the Navy. pp. 1-2. Docket "Entry and Education of Naval Officers". The National Archives. ADM 1/7875.

- ↑ Ibid. pp. 2-3.

- ↑ Undated Ottley minute. Docket "Entry and Education of Naval Officers". The National Archives. ADM 1/7875.

- ↑ Entry and Training of Officers of the Navy. p. 3.The National Archives. ADM 1/7992.

- ↑ Ibid. pp. 4-5.

- ↑ Custance Committee. p. 54.

- ↑ Custance Committee. p. 22.

- ↑ Custance Committee. p. 22..

- ↑ Hansard. HC Deb 18 February 1941 vol 369 cc32-6.

- ↑ Hansard. HC Deb 07 May 1947 vol 437 cc423-8.

- ↑ Johnson. "Class Warfare and the Selborne Scheme." pp. 431-432.

- ↑ Davies. "The Selborne Scheme" in Hore. Patrick Blackett. p. 26.

- ↑ Selection of Candidates for Nomination as Naval Cadets. Cd. 2450. p. 11.

- ↑ Davies. p. 26.

- ↑ Davies. p. 35. Hamilton service record. The National Archives. ADM 196/45/22. Sherwood service record. The National Archives. ADM 196/148/346.

- ↑ Marder. p. 47.

Bibliography

- A Statement of Admiralty Policy. Cd. 2791. 1905.

- Memorandum Dealing with the Entry, Training, and Employment of Officers and Men of the Royal Navy and of the Royal Marines. Cd. 1385. 1902.

- Report of the Departmental Committee Appointed to Consider Various Questions Concerning the Engineer Officers of the Navy and the Officers of the Royal Marines [Douglas Committee]. 1907. Copy No. 25 at The National Archives. ADM 116/862.

- Reports of the Committee Appointed to Enquire into the Education and Training of Cadets, Midshipmen and Junior Officers of His Majesty's Fleet; Together with Enclosures [Custance Committee]. Cd. 6703. 1913.

- Return, for the Year ended 31st March 1904, of the Army and Navy Officers Permitted, Under Rule 2 of the Regulations drawn up under Section 6 of the "Superannuation Act, 1887," to hold Civil Employment of Profit under Public Departments. H.C. 319, 1904.

- Return, for the Year ended 31st March 1911, of the Army and Navy Officers Permitted, Under Rule 2 of the Regulations drawn up under Section 6 of the "Superannuation Act, 1887," to hold Civil Employment of Profit under Public Departments. H.C. 234, 1911.

- Selection of Candidates for Nomination as Naval Cadets. Reports of Members of the Interview Committees. Cd. 1962. 1904.

- Selection of Candidates for Nomination as Naval Cadets. Further Reports of Members of the Interview Committees. Cd. 2450. 1905.

- The Entry and Training of Naval Officers. 1914.

- Blackett, Patrick (2005). "Boy Blackett". In Hore, Peter (ed.). Patrick Blackett: Sailor, Scientist and Socialist. London: Frank Cass. pp. 1-14. ISBN 0-7146-5317-9.

- Bush, Eric Wheeler (1958). Bless Our Ship. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- Davies, Evan (2005). "The Selborne Scheme: The Education of the Boy". In Hore, Peter (ed.). Patrick Blackett: Sailor, Scientist and Socialist. London: Frank Cass. pp. 15-36. ISBN 0-7146-5317-9.

- Johnson, Oliver (2014). "Class Warfare and the Selborne Scheme: The Royal Navy's battle over technology and social hierarchy". The Mariner's Mirror. 100:4. pp. 422-433. DOI:10.1080/00253359.2014.962327.

- Marder, Arthur J. (1961). From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow, The Royal Navy in the Fisher Era, 1904-1919: The Road to War, 1904-1914. Volume I. London: Oxford University Press.

| Term Intakes into Royal Naval College, Osborne |

| Before 1905, new Naval Cadets went to H.M.S. Britannia |

| 1903-1909 |

| Sep, 1903 | Jan, 1904 | May, 1904 | Sep, 1904 | Jan, 1905 | May, 1905 | Sep, 1905 | Jan, 1906 | May, 1906 | Sep, 1906 Jan, 1907 | May, 1907 | Sep, 1907 | Jan, 1908 | May, 1908 | Sep, 1908 | Jan, 1909 | May, 1909 | Sep, 1909 |

| 1910-1914 |

| Jan, 1910 | May, 1910 | Sep, 1910 | Jan, 1911 | May, 1911 | Sep, 1911 | Jan, 1912 | May, 1912 | Sep, 1912 Jan, 1913 | May, 1913 | Sep, 1913 | Jan, 1914 | May, 1914 | Sep, 1914 |

| 1915-1919 |

| Jan, 1915 | May, 1915 | Sep, 1915 | Jan, 1916 | May, 1916 | Sep, 1916 | Jan, 1917 | May, 1917 | Sep, 1917 Jan, 1918 | May, 1918 | Sep, 1918 | Jan, 1919 | May, 1919 | Sep, 1919 |

| This is generally the end of our Scope |