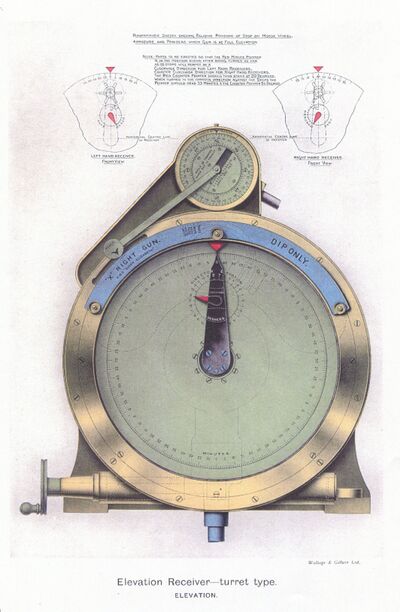

Turret Type Elevation Receiver

The Turret Type Elevation Receiver was a component of the British Tripod Director Firing System employed in their capital ships in the Great War period. It told the Gunlayers by Follow-the-Pointer indications the elevation angle the director wanted on the guns.

Design and Function

Elevation receivers displayed an indication of the desired elevation angle (being transmitted from the Gunnery Director) for the gun, quantized in steps of 1.5 arc minutes, and could apply corrections for:

- Tilt to negate imperfection in the mounting's vertical installation.

- Dip (differences in mounting height relative to the ship's datum point).

- The muzzle velocity in the particular gun, subject to its accumulated number of firings.

- Use of alternate projectiles or reduced charges.

The communicated elevation was indicated by the movement of two red pointers. One pointer, on a small dial, conveyed the coarse angle in degrees. Another red pointer traced the circumference of the large dial that formed the bulk of the instrument to indicate the angle more finely at six degrees per revolution. By elevating his weapon using his hydraulic controls, the layer would see black pointers move in response. When the black pointers matched the red ones, the proper elevation was on the weapon.

Before action commenced, the gun layer was also tasked with selecting (from several provided each gun) and fitting the proper "dip strip", a partial cirumferential meter on the face of the receiver to reflect the present muzzle velocity his weapon would deliver using the specified projectile and charge being employed. For instance, the gun might be using full charges and 4 C.R.H. shells, and have lost 60 feet per second muzzle velocity due to wear sustained from previous firings. The strip most nearly matching this description would be fastened in position using frictional screws.

The gun layer's primary task in action would be to work his elevating control gear so that his gun's actual elevation (which he saw on the receiver by the position of two black pointers) would match the elevation being signaled from the director, which was indicated on the receiver by the position of two red pointers. This design was called Follow-the-Pointer, and was the best model of the time to avoid human error in establishing the proper gun elevation.

A secondary task required of the gun layer in action was to keep the present range to the target, which he would receive verbally, entered on the receiver by a small handwheel. Entering the range in such a manner would rotate the assembly upon which the dip strip was mounted so that the corrections listed above would be applied when the red and black pointers were in agreement.

Tilt Corrector

Though there was a finite tolerance for such construction imperfection, it had to be accepted that a large and extremely heavy turret was never mounted perfectly within the structure of the ship. Most vitally, its training axis would not point perfectly "upward". The result of this tilted installation was that, when the guns were laid to zero elevation and the turret revolved through its entire envelope of training angles, the guns' elevation relative to the horizon would vary in a mild sinusoid about the desired true level. This could be characterized by citing the maximum positive deviation in elevation angle (let's call this E), and the training angle (T) at which it occurred. A training angle 180 degrees opposed to T would have an elevation error of -E, and the guns would be perfectly level (E = 0) at the two training angles T +/- 90 degrees.

Each turret, it could be expected, would have different values of T and E. Because the equipment within a gun mounting measured elevation relative to the mounting, and not to the ship, salvoes fired at any angle of bearing would result in shots coming out at a variety of elevations.

A small housing atop the elevation receiver's chassis contained the Tilt Corrector, a dial which spun around to mimic the training angle of the mounting. This small rotor had an equitorial slot which could be, in the dockyard where such alignments could be precisely measured, spun to indicate T, and along this slot, a pin could be fixed to a position proportional to E. This pin formed a pivot point for an arm with a circular paddle with an index mark on it on the other end which could lazily ride on the circumference of the receiver. You can envision the result of this assembly: as the tilt corrector rotated to mimic the training of the turret, the index on the paddle would trace back and forth in a sinuous manner around the edge of the receiver with a magnitude proportional to E. By choosing the scale of the markings for all graduated elements involved, the position of the index, when matched by use of a range-setting handle on the lower left of the receiver, would cancel out the tilt error. The exact manner of the etching of each dip strip could also address the other errors in the table above. It was a fairly ingenious mechanism.

Director Tilt, Dip, etc

It bears mention that correcting for tilt and dip and such at the turret makes no sense unless the director's own emplacement enjoyed similar treatment and correction. This was of course the case. All were attuned to a common "reference plane" aboard the ship.

See Also

Footnotes