Annual Manoeuvres of 1894

The Royal Navy's Annual Manoeuvres of 1894 were planned to operate over a maximum of ten days, and were a development of those of the previous two years.[1]

Planning

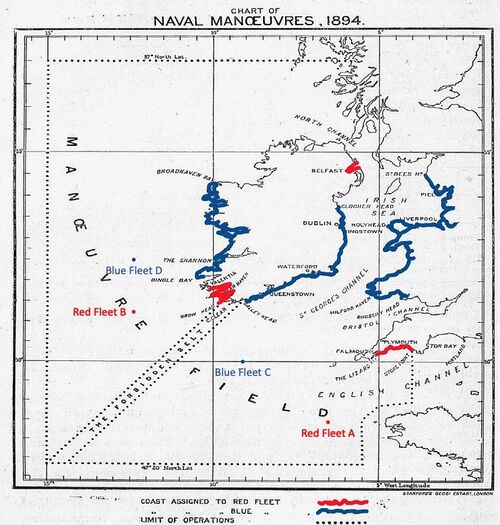

Each of the two opposing fleets were themselves divided into two, as listed below, with the manoeuvre field being off the west coast of Britain out as far as 15º west, and between 57º and 47º 20’ north. The umpires were Admiral Sir W. Hunt-Grubbe, Rear-Admiral James E. Erskine and Rear-Admiral Hilary G. Andoe.

On 2 August each of the four fleets proceeded to a pre-arranged rendezvous location, known only to their own side, with the knowledge that hostilities would start at 9am the following morning.

Each of the fleets was allocated a strength value determined by the classification of the ships present: first-class battleships counted as five points and second-class battleships as four points; cruisers counted as one point and smaller ships zero. For any engagement between fleets to be counted as decisive the superior force had to exceed the opponent by at least one-ninth of the latter’s strength. Both of Red’s fleets were worth 32 points, whereas Blue’s fleets were 38 and 19 points.

The two commanders were not given specific instructions, merely being informed that they were at war and the composition of their opponent. From the strength points above it can be seen that each of Red’s fleets was vulnerable to Blue’s larger fleet, so Red might choose to combine before seeking battle. Blue would have to decide whether to engage one of Red’s fleets or attempt to combine in order to protect its weaker fleet. This would likely prove difficult as Red held the speed advantage. If the Red fleets were allowed to rendezvous, they would be superior to anything Blue could oppose them with. Although the Red fleets held the advantage of speed, the Blue fleets were closer to each other and had the advantage of interior positions.

Events

Rear-Admiral Edward H. Seymour, the Blue commander, chose to combine his two fleets as quickly as possible whereas Vice-Admiral Robert O'B FitzRoy delayed the union of the Red fleets. Although his B fleet was ordered to sail at best speed to achieve a rendezvous, he delayed sailing his A fleet into St George’s Channel until nightfall and, even then, he sent his cruisers ahead of the main A Fleet in the expectation that they would be mistaken for his main fleet and draw off the enemy battlefleet. These cruisers were to rendezvous with the B Fleet while the main body of the A Fleet was 3½ hours behind them.

As a results of Vice-Admiral FitzRoy’s strategy, the Blue C fleet was able to pass through St George’s Channel twelve hours ahead of the Red Fleet cruisers, and rendezvoused with the D Fleet five miles off the Isle of Man. The combined Blue Fleet then proceeded north towards the North Channel but intercepted the B Red Fleet several miles north of the entrance to Belfast. Heavily outnumbered, Rear-Admiral Alfred T Dale, in charge of the B Fleet, sailed for Belfast reaching it safely and avoiding defeat. However, according to the rules, in passing close to the ‘neutral’ coast in order to do so, he rendered the B Fleet out of action for 24 hours.

At this point Rear-Admiral Seymour took his combined Blue Fleet south again to search out the Red A Fleet. He encountered Red’s cruisers which were waiting at the rendezvous for the B Fleet, with the rest of the A fleet not far behind. Seeing themselves outnumbered the Red A Fleet headed for Belfast but Vice-Admiral FitzRoy then turned to give battle when he saw the B Fleet leaving Belfast and also approaching the Blue Fleet. The opposing sides gave battle for the two hours required by the rules and both sides claimed decisive victory. After some deliberation, the umpires awarded victory to the Blue Fleet as the Red B Fleet had been deemed out of action and was not in a position to give battle.

Analysis

Despite having been allocated ten days, the manoeuvres were concluded within 36 hours. This was seen by the historian J. R. Thursfield as both advantageous, as the conclusions were clear-cut, but disadvantageous as there was little opportunity for education or training.

Thursfield pointed out that the geography was analogous to a compressed version of the Mediterranean, representing a war between Britain and France. The coastline allocated to the Blue forces could be taken to represent France’s Mediterranean coast and her possessions in north Africa from the Moroccan border to Tripoli. By the same analogy Queenstown represented Toulon, he asserted, Falmouth Malta, Berehaven Plymouth, the Shannon Brest and Belfast Gibraltar. Where the analogy falls down is that the scaled distances were only one-third of the real distances.

Rear-Admiral Dale’s actions of running the Red B Fleet into Belfast was open to much criticism as it was suggested that he had broken two of the rules of the manoeuvres, namely that:

- No ship is to approach within eight cables of an enemy’s ship; and

- Ships or torpedo boats entering neutral waters, or communicating in any way with the shore in neutral territory, are to be out of action for twenty-four hours.

In order to enter Belfast Lough, Rear-Admiral Dale’s fleet both came within eight cables of the enemy, and passed close to the Maidens, a detached and uninhabited rock off the Irish coast, deemed to be neutral territory. It is this latter violation which made B Fleet’s subsequent attack on the combined Blue Fleet invalid.

Thursfield argues that it might have been a better course of action for Dale to head north upon sighting the Blue Fleet and escaped using his superior speed. This would not have ruled out the possibility of a later rendezvous with Red Fleet A off the west coast of Scotland.

Order of Battle

The ships to be called up at Portsmouth especially for the manoeuvres in July were to include: Royal Oak, Naiad, Latona, Intrepid, Iphigenia, Indefatigable, Iris, Calliope and Rattlesnake.[2]

A complete roster of ships with their appointed captains appeared in The Times on 12 July,[3] and their organization appeared as follows on 18 July, the official date of the appointments.[4]

Outcome

Stories on the manoeuvres also appeared in The Times on the 18th of July[5] and the 20th.[6]

Footnotes

- ↑ Most of the information here is taken from J R Thursfield “British Manoeuvres in 1894”, in Brassey’s Naval Annual 1895 (Portsmouth: J Griffin & Co., 1895).

- ↑ "Naval & Military Intelligence." The Times (London, England), Friday, Jun 08, 1894; pg. 10; Issue 34285.

- ↑ "The Naval Manoeuvres." The Times (London, England), July 12, 1894, Issue 34314, p.10.

- ↑ "The Naval Manoeuvres of 1894." The Times (London, England), July 18, 1894, Issue 34319, p.13.

- ↑ "The Naval Manoeuvres of 1894." The Times (London, England), July 18, 1894, Issue 34319, p.13.

- ↑ "The Naval Manoeuvres." The Times (London, England), July 20, 1894, Issue 34321, p.12.

| Annual Manoeuvres of the Royal Navy |

| 1880s |

| 1880 | 1881 | 1882 | 1883 | 1884 | 1885 | 1886 | 1887 | 1888 | 1889 |

| 1890s |

| 1890 | 1891 | 1892 | 1893 | 1894 | 1895 | 1896 | 1897 | 1898 | 1899 |

| 1900s |

| 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 |

| 1910s |

| 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 |