Selborne Scheme

The Selborne Scheme (also known as the Selborne-Fisher Scheme) was introduced in 1903 whereby the Royal Navy consolidated initial entry and training for officers of the Military Branch, Engineer Branch and Royal Marine Forces into one Common Entry (by which name the scheme was also known). The scheme was named for the First Lord of the Admiralty of the day, the Earl of Selborne, although the driving force behind the scheme was the Second Sea Lord, Admiral Sir John A. Fisher.

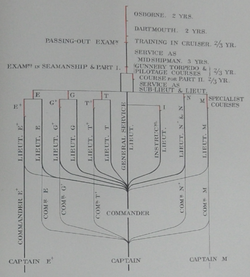

Boys entered as Naval Cadets between the age of 12 and 13 studied for two years at the Royal Naval College, Osborne, two years at Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, and a period in a training cruiser at sea before joining the Fleet as Midshipmen. After three to two years' sea service the teenagers could then qualify for the rank of Acting Sub-Lieutenant, confirmed after passing all examinations for the rank of Lieutenant. As Lieutenants they could then specialise in gunnery (G), torpedo (T) and navigating (N) duties as normal (and eventually signalling (S) duties). The Selborne Scheme introduced the specialisation of engineering (E) would have created that of military (M), i.e. Marine.

As envisaged the officers of the various specialisations were meant to be interchangeable, and allowed to revert to general duties by the rank of Captain. However, it was planned that engineering officers could elect to specialise further as (E†) and remain specialists for the remainder of their career, or Commanders (M) could remain in marine line and be promoted to Captain (M).

The last separate entry for the Royal Marines was made in June, 1907, but was reintroduced in 1911. When the first of the New Scheme began to specialise in 1913 two Sub-Lieutenants volunteered for service with the Marines but became Probationary Lieutenants, Royal Marines, rather than Sub-Lieutenants (M).

In 1922 selection for engineering specialisation was introduced at the rating of Midshipman, at which point those selected went to the Royal Naval College, Keyham for four years' study. In 1925 engineering again became a separate branch with purple distinction braid between the stripes. (E) officers were compelled to revert to the executive branch or remain.

Background

Selborne told the House of Lords in 1926:

The scheme of 1902 is generally known as the Selborne-Fisher scheme, but it would be much more correct to call it the Selborne-Kerr-Fisher scheme, because Admiral of the Fleet Lord Walter Kerr, who I am glad to say is still with us to-day, was the First Sea Lord. Lord Fisher was Second Sea Lord. Lord Walter Kerr was an officer of the old school who never would dream of agreeing to a change on mere grounds of theory. He would never agree unless he thought an important change was essential to the good of the Service. I think a great deal too much stress has been laid on Lord Fisher's name in this matter. Lord Walter Kerr was just as responsible for the scheme as Lord Fisher, but Lord Fisher, as the Second Sea Lord, was the particular member of the Board of Admiralty who had the work of administering the scheme. Under that scheme there was to be a common entry for all the officers of the Navy, and they were to specialise when they reached the rank of Lieutenant, and decide whether they would become engineer officers or not.[2]

Main Features

In his memorandum of 16 December, 1902, the First Lord of the Admiralty, the Earl of Selborne announced:

It has been decided henceforth—

1. All Officers for the Executive and Engineer branches of the Navy and for the Royal Marines shall enter the Service as Naval Cadets under exactly the same conditions between the ages of 12 and 13;

2. That these Cadets shall be trained on exactly the same system until they shall have passed for the rank of Sub-Lieutenant between the ages of 19 and 20;

3. That at about the age of 20 these Sub-Lieutenants shall be distributed between the three branches of the Service which are essential to the fighting efficiency of the Fleet—the Executive, the Engineer, and the Marine.[3]

Ages of Entry

In the first entry in September, 1903, the limits of age were 12 to 13. The reason given by Selborne was that:

the age of 12 to 13 not only corresponds to that at which the history of the Navy shows that boys have been most successfully moulded to sea character, but also it corresponds to the age at which boys leave Private Schools and, therefore, to a natural period in the system of education which obtains in this country.[4]

For the next entry, January, 1904, the lower limit of age was raised to 12 years and four months.[5] In 1906 the lower limit was raised by another four months to 12 years eight months.[6] The Custance Committee in its third report of September, 1912, specifically advised against raising the lower limit any further.[7] However, in November, 1913, the lower and upper limits were narrowed to 13 years four months and 13 years eight months respectively, taking effect in January, 1914.[8]

Nomination and Appointment

"Appointments to Naval Cadetships will be made by nomination subject to the nominees passing a qualifying examination. Candidates who fail to pass will not be allowed a second trial."[9]

Baddeley claimed before the Custance Committee that "The word 'Nomination' no longer exists. That is abolished."[10] The term was still in use then, however. It was not until the end of 1913 that the regulations were amended:

No nomination is required by a Candidate for a Naval Cadetship. All that is necessary is to send an application to the Assistant Private Secretary to the First Lord of the Admiralty.[11]

Interviews

All candidates except Colonial Candidates had "to present himself before a Committee, which will interview each applicant separately". Nominations were then given by the First Lord to the candidates recommended by the committee. A committee was usually presided over by a senior flag officer and comprised a second naval officer, an educator such as the head master of a public school, and a member of the First Lord's Private Office.

A system of grading was utilised by the first five committees:[12]

| Category. | Classification. |

|---|---|

| Fit. | α+, α, α- |

| Doubtful, though promising. | β+, β, β- |

| Unsuitable. | γ |

Lord Helmsley, the First Lord's political Private Secretary, thought that in some cases it was too difficult to classify some of the boys using + and - signs, and proposed five classifications A, B, C, D, E, where C represented the average.[13] However, according to Vincent W. Baddeley, Assistant Private Secretary to the First Lord, on the sixth committee which sat in February, 1905: "The present Committee found that so far from having much difficulty in classifying the candidates, it could safely subdivide the large middle or β Class still further".[14] This resulted in the following classification of that committee's results:[15]

| α+ | 2 | good β+ | 5 | good β | 25 | β- | 19 |

| α | 8 | β+ | 28 | β | 38 | γ | 19 |

| α- | 13 | poor β+ | 7 | poor β | 6 |

Oliver Johnson has claimed that:

the more experience the interview panels gained, the more they would diverge from the script to gauge the background of the candidate, with questions including 'with what should one eat caper sauce, apple sauce or currant jelly', how to address a king, duchess or bishop and how much a piece of luggage cost to carry in a cab. Although well-intentioned, the scheme was quickly corrupted to preserve the privilege that the opponents of the scheme defended so vociferously.[16]

As is so often the case Johnson was borrowing text from another source, in this instance Evan Davies' chapter in a volume on the scientist-sailor Patrick Blackett (Johnson declined to attribute the author of the chapter, only the editor). Davies wrote:

As the committees became more experienced, they moved a little from the script. It is fairly easy to see that asking a 12-year-old what was the lowest London cab fare or how much a piece of luggage cost to carry in a cab, or what sort of animals or birds would be regarded as game in this country, or with what he should eat caper sauce, apple sauce or currant jelly, or how he should address a duchess, a king or a bishop could establish social background. The connection between that last question and the relative performance of clergymen's and doctors' sons is pretty obvious. He was to be asked other questions that more directly addressed general knowledge, like 'What are the chief agricultural crops grown in England?' though the landed interest might benefit from that one, or 'What are the principal railways of England?'. There are some imperialist questions, like asking for names of eight of England’s colonies or six island colonies of the British Empire. Some are more directly naval: 'What is [sic] a lightship and a buoy and what are they used for?'[17]

The reference to moving "a little from the script" comes from Canon The Honourable Edward Lyttelton, Head Master of Haileybury (soon to become Head Master of Eton College), who wrote after the November, 1904, committee, "I think we gradually learnt how to depend less on set questions and more on making the boys talk freely, in tempting them to with sufficient questions to see if they knew what they were saying."[18] As to reading class into the questions, the author suspects that Davies is on very thin ice with a handful of examples from 1903. The plural of anecdote is not data. The less said about Johnson's cherry picking and borderline plagiarism the better.

Qualifying Examination

In the original memorandum it was stated:

The entrance examination for the Royal Naval College, commonly known as the "Britannia" examination, will be of an elementary kind, and confined to those subjects in which a carefully-educated boy has usually been instructed up to the age of 13. No change will be made in the present system of entering boys for the competition, but the medical advice is conclusive that at this early age the examination must not be severe, and indeed that no examination of boys at this age or at the later age now obtaining can be considered an accurate test of what their comparative faculties will be when they have attained manhood.[19]

The qualifying examination as established comprised six subjects:

(1.) English—(including writing from dictation, simple composition and reproduction of the gist of a short passage twice read aloud to the Candidates.)

(2.) History and Geography, with special reference to the British Empire.

(3.) Arithmetic and Algebra (to Simple Equations).

N.B.—Two-thirds of this paper will be in arithmetic.

(4.) Geometry (to include the subject matter of the First Book of Euclid, or its equivalent, with simple Mensuration. The use of instruments is allowed.

(5.) French or German, with an oral examination, to which importance will be attached.

(6.) Latin (easy passages for translation from Latin into English and from English into Latin, and simple grammatical questions).[20]

Length of Training

In Selborne's 1902 memorandum it was envisaged that "Cadets will remain under instruction at the Royal Naval College for four years before going to sea".[21]

In response to the mounting shortage of officers Churchill proposed to Jellicoe on 10 March, 1914, that an option for relief might be to "Reduce the classes [sic] at Osborne from six to five, and fill up by new entries."[22] At a Board meeting of 26 March "Increase of Cadet Colleges and accommodation of Cadets discussed. As a principle Colleges to be organised on scheme of five terms at Osborne and six at Dartmouth."[23]

Specialisation

It was made clear at the start that officers might have to join a branch they did not want:

No nominations will be given to boys whose parents or guardians do not declare for them that they are prepared to enter any one of the three branches of the Service at the termination of their probationary period of service afloat.

As far as possible each Officer will be allowed to choose which Branch or Service he will join, but this must be subject to the proviso that all alike are satisfactorily filled.[24]

End of the Scheme

The last entry of officers for the Royal Marines under the old scheme took place in June, 1907. In 1911 it was decided to restart separate entries, with 11 joining in January, 1912 as Probationary Second Lieutenants, Royal Marines. In 1912 two Sub-Lieutenants volunteered for marine duties and joined the Royal Naval College, Greenwich as Probationary Lieutenants, Royal Marines, and not as Sub-Lieutenants (M). Charles H. Congdon retired as a Lieutenant-Colonel and Robert G. Sturges was knighted and reached the rank of Lieutenant-General. These were the only two Selborne Scheme entrants to ever join the Marines.

Reactions

Captain Rosslyn Wemyss of Osborne noted in a 1905 letter to Fisher:

[A] tendency on the part of the parents of some of the cadets at Osborne to hope at least that their sons might never become Lieutenants (E), with no chance of commanding ships or fleets, and I have a suspicion that, that for this reason, they have in some cases even discouraged their sons in their engineering studies.[25]

Speaking before the Douglas Committee in 1906, Admiral Sir Lewis A. Beaumont, Commander-in-Chief, Plymouth, opined:

The fundamental change which has been brought about by the common entry has already disturbed the Service in a great measure, and, speaking for myself, I do not think that it has the good will of the Service generally. I do not mean the common entry alone, but what follows from common entry.[26]

In their minority report on the Douglas Committee, Rear-Admiral Login, Commodore Briggs and Captain Bacon, in opposing the inclusion of the Engineer Branch in the Military Branch, made direct reference to the Selborne Scheme reforms:

As officers in touch with the sea-going Fleets, we would also remind their Lordships that the great changes which have taken place in the Navy during the past two years have created a great feeling of unrest and uncertainty which only loyalty has in a measure recently soothed. It is very undesirable, therefore, to introduce at the present moment any further important changes which are not absolutely necessary.[27]

Rear-Admiral Hugh Evan-Thomas, Captain of Dartmouth, whilst adamantly against change, believed that in order to give boys an extra eight months at school the age of entry could be increased to 13 years and six months, and the number of terms reduced from 12 to ten: five at Osborne and five at Dartmouth.

Results

Executive

The first officer from Osborne promoted to the rank of Captain was Harold T. C. Walker on 31 December, 1931.[28][29]

Engineers

The first 17 officers selected to specialise in engineering were appointed to the Royal Naval College, Greenwich, on 1 October, 1913.[30] The first promotions to the rank of Captain (E) occurred on 30 June, 1936, with the promotion of John B. Sidgwick and Denys C. Ford, who had entered Osborne in January, 1904, and September, 1903, respectively.[31]

Assessment

There can be no doubt that there was strong opposition to the Selborne scheme. However, what Marder termed "objections of a snobbish nature" aside, it is also clear that much opposition was based on incorrect information regarding the scheme. It is all very well for Marder to damn "people who had not informed themselves as to the real nature of the Admiralty scheme",[32] but it suggests a real failure on the part of the Admiralty to present the case for and the details of the Selborne Scheme not only to the public but to the Navy itself.

Footnotes

- ↑ The New Scheme of Naval Training. Lecture by the Director of Naval Education. 11th May 1906. p. 23/

- ↑ Hansard. HL Deb 14 July 1926 vol 64 cc1075-76.

- ↑ Memorandum Dealing with the Entry, Training, and Employment of Officers and Men of the Royal Navy and of the Royal Marines. pp. 3-4.

- ↑ Memorandum Dealing with the Entry, Training, and Employment of Officers and Men of the Royal Navy and of the Royal Marines. p. 4.

- ↑ Report of the Director of Naval Education, for the Year 1904. p. 4.

- ↑ Report of the Director of Naval Education for the Year 1906. p. 4.

- ↑ Custance Committee. Third and Main Report. p. 23.

- ↑ The Navy List, Corrected to the 18th March, 1914. pp. 856-861.

- ↑ The Navy List, for October, 1904, Corrected to the 18th September, 1904. p. 879.

- ↑ Custance Committee. p. 168. Q. 4516x.

- ↑ The Navy List, for April, 1914, Corrected to the 18th March, 1914. p. 856.

- ↑ Selection of Candidates for Nomination as Naval Cadets: Reports of Members of the Interview Committees. p. 5. Selection of Candidates for Nomination as Naval Cadets: Further Reports of Members of the Interview Committees. p. 12.

- ↑ Selection of Candidates for Nomination as Naval Cadets: Further Reports of Members of the Interview Committees. p. 12.

- ↑ Selection of Candidates for Nomination as Naval Cadets: Further Reports of Members of the Interview Committees. p. 17.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Johnson. "Class Warfare and the Selborne Scheme." pp. 431-432.

- ↑ Davies. "The Selborne Scheme" in Hore. Patrick Blackett. p. 12.

- ↑ Selection of Candidates for Nomination as Naval Cadets: Further Reports of Members of the Interview Committees. p. 11.

- ↑ Memorandum Dealing with the Entry, Training, and Employment of Officers and Men of the Royal Navy and of the Royal Marines. p. 4.

- ↑ The Navy List, for October, 1904, Corrected to the 18th September, 1904. p. 879.

- ↑ Memorandum Dealing with the Entry, Training, and Employment of Officers and Men of the Royal Navy and of the Royal Marines. p. 4.

- ↑ First Lord's Minutes. Volume II. Dec. 1913 to May 1915. p. 35.

- ↑ "Board Minutes. Thursday, 26 March 1914." The National Archives. ADM 167/48.

- ↑ The Navy List, for October, 1904, Corrected to the 18th September, 1904. p. 879.

- ↑ Quoted in Marder. p. 47.

- ↑ Douglas Committee. p. 127.

- ↑ Douglas Committee Report. ADM 116/862. pp. 43-44.

- ↑ "Royal Navy" (Official Appointments and Notices). The Times. Friday, 1 January, 1932. Issue 46019, col B, p. 16.

- ↑ "Royal Navy" (Official Appointments and Notices). The Times. Thursday, 14 January, 1932. Issue 46030, col G, p. 6.

- ↑ "Royal Navy" (Official Appointments and Notices). The Times. Friday, 18 August, 1933. Issue 46526, col F, p. 5.

- ↑ "Royal Navy" (Official Appointments and Notices). The Times. Thursday, 2 July, 1936. Issue 47416, col F, p. 25.

- ↑ Marder. p. 47.

Bibliography

- Marder, Arthur J. (1961). From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow, The Royal Navy in the Fisher Era, 1904-1919: The Road to War, 1904-1914. Volume I. London: Oxford University Press.