Bellerophon Class Battleship (1907)

The three Bellerophon class dreadnoughts were designed as a follow-up to the revolutionary H.M.S. Dreadnought.

Dreadnought's secondary armament was deemed insufficient to fight close quarter battle with enemy Torpedo Boat Destroyers, and the three ships were given heavier guns. Their internal sub-division was improved to decrease the possibility of sinking from mine or torpedo attack. Unlike Dreadnought the Bellerophon class were given two tripod masts, with two control tops. This was ostensibly to improve sea-keeping capability, but with the main mast just forward of the second funnel, it was frequently inundated with smoke and proved nearly useless in bad weather.

The three ships of the class performed service with the Grand Fleet for much of the First World War, and in 1918 Superb and Temeraire were dispatched to the Eastern Mediterranean for service against the Ottoman Empire. Due to their inferior main armament, all three ships were immediately relegated to non-active duties following the Armistice, and were scrapped during the course of the 1920s.

The ships were visually similar to their successors, the St. Vincents, but can be recognized by their shorter funnels of equal size.[1]

The guns for each cost £116,300, contributing to total costs below.[2]

| Overview of 3 vessels | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citations for this data available on individual ship pages | |||||

| Name | Builder | Laid Down | Launched | Completed | Fate |

| Bellerophon | Portsmouth Royal Dockyard | 3 Dec, 1906 | 27 Jul, 1907 | 20 Feb, 1909 | Sold 8 Nov, 1921 |

| Superb | Armstrong, Whitworth & Company, Elswick | 6 Feb, 1907 | 7 Nov, 1907 | 29 May, 1909 | Sold 12 Dec, 1922 |

| Temeraire | Devonport Royal Dockyard | 1 Jan, 1907 | 24 Aug, 1907 | 1 May, 1909 | Sold 7 Dec, 1921 |

Binoculars

In September 1914, the ships were allowed two additional pairs of Pattern 343 Service Binoculars.[3]

Radio

According to the ambitions of 1909, these ships had Service Gear Mark II wireless upon completion.[4]

Armament

In early 1913, new pattern G. 329 trainer's telescopes of 2.5 power and 20 degree field were issued to these and many other capital ships, to replace the 5/12, 5/15 and 5/21 variable power G.S. telescopes that had previously been in use.[5]

Main Battery

This section is sourced in The Sight Manual, 1916.[6]

The ten 12-in guns were Mark X mounted in B. VIII* turrets. The mountings could elevate 13.5 degrees[7] and depress 5 degrees.

The gun sights were gear-worked sights with a range gearing constant of 48 and limited to 15 degrees elevation, but 6 degree super-elevation prisms would have been provided by 1916. They were the last Royal Navy dreadnoughts to use telescopes, rather than periscopes, in their turret sights.

The deflection gearing constant was 70, with 1 knot equalling 2.52 arc minutes, calculated as 2700 fps at 5000 yards. Range drums were provided for full charge at 2625 fps, reduced charge at 2250 fps, as well as 6-pdr sub-calibre gun and .303-in aiming rifles.

Muzzle velocity was corrected by adjustable pointer between +/- 75 fps. The adjustable temperature scale plate could vary between 60 to 100 degrees Fahrenheit,[Fact Check] and a "C" corrector could alter the ballistic coefficient by +/- 20%.[Fact Check]

Deflection was corrected by inclining the sights (in the centre position only) by 2 degrees and by the additional use of 1 knot permanent left deflection when firing 4 CRH projectiles.

The side position sighting lines were 36 inches above and 42 inches abreast the bore, and the central scopes were 37.5 inches above and 42 inches abreast. The left-hand centre position sight was a free trainer's sight, able to swing freely in pitch.

An arrow was cut in the deflection dial at 1 knot right and inscribed, "Zero for sight testing."[8]

The hydraulic controls in training reflected recent advances from Indomitable though progress was to continue; operated by a single handwheel driving a six cylinder rotary engine, they could permit continual aim at speeds up to 3 degrees per second.[9]

The original storage was 80 rounds per gun: 24 A.P., 40 Common and 16 Lyddite.[10].

Secondary Battery

This section is sourced in The Sight Manual, 1916.[11]

Sixteen 4-in B.L. Mark VII guns on P. II mountings were arranged for broadside fire. They were similar the the P. II* equipment fitted in the St. Vincent, Neptune, Indefatigable classes and other ships.

The mounting could elevate 15 degrees and depress 7 degrees, but though its sight could match the 15 degree elevation, the range dial was only graduated to 11.5 degrees (10,000 yards).

These first-ever cam-worked sights had range dials for 2750 fps, and 1-in and .303-in aiming rifles. MV could be corrected by adjustable pointer through +/- 150 fps.

The range dial was 14 inches in diameter with markings that came closer together at higher ranges. The marks were 3⁄4 inch apart for 50 yards difference at 500 yards and was 1⁄8 inch for 50 yards difference at 9,000 yards.

The deflection gearing constant was 64.277 with 1 knot equal to 2.41 arc minutes, corresponding to 2800 fps at 2000 yards. Drift was corrected by inclining the sight 2 degrees.

The layer's sight line was 14 inches above the bore, and 15.25 inches left. The trainer's sight line was 14 inches above and 12.5 inches right.

The sight had both temperature and "C" correctors.

The layer had an open sight. Neither side was a free sight.

In February, 1913, these mountings, along with many other 4-in and 6-in mountings in capital ships were to have illumination added for their training index racers.[12] In August of that 1913, Portsmouth Royal Dockyard was to supply head rests for these guns, to be fitted by the ships' artificers.[13]

The original storage was 200 rounds per gun (,[14] but after the Battle of Jutland, when alterations to increase protection forced weight-savings to compensate, the ammunition allotment for these guns was to be reduced to 150 rounds per gun and 6 shrapnel rounds.[15]

Torpedoes

The ships carried three submerged 18-in tubes:[16]

- two forward, depressed 1 degree and angled 15 degrees before the beam, axis of tube 11 foot 6.625 inches below load water line and 2 foot 5 inches above the deck.

- one in the stern, depressed 1 degree; axis of tube 8 feet 6 inches below load water line and 1 foot 9 inches above the deck.

In 1909, it was decided that ships of this class were to carry 10 heater torpedoes, distributed with eight in the broadside submerged flat and two at the stern tube. The goal, when supplies were made good, was to have the ten heaters be Mark VI* H. or Mark VI** H..[17]

In 1913, it was approved as part of a general reallocation of 18-in torpedoes, to replace the Mark VI** H. or 18-in Mark VI*** H. torpedoes on Neptune, St. Vincent, Bellerophon and Dreadnought classes with with Mark VII* or Mark VI**.[18] The Admiralty had simultaneously imposed a limit of gyro angle settings of 20 degrees in these same ships. This restriction was lifted just before the war.[19]

Fire Control

Rangefinders

The ships had seven rangefinders as completed: a 9-ft[Inference] in each turret roof and a pair of rangefinders astride the aft boat deck.[20]

Sometime during or after 1917, an additional 9-foot rangefinder on an open mounting was to be added specifically to augment torpedo control.[21]

Evershed Bearing Indicators

Bellerophon and Temeraire were fitted with this equipment before late 1914, but it is not clear whether Superb was included in this.[22]

Transmitting positions were

- Fore control platform (transmitters to port and starboard with C.O.S. to select one in use)

- "A" turret

- "Y" turret

- Upper aft conning tower

The protocols for handling wooding of the turrets is outlined in the Handbook for Fire Control Instruments, 1914.[23]

In 1917, it was approve that capital ships of Dreadnought class and later should have Evershed equipment added to their C.T., able to communicate with either the fore top or a controlling turret. If there were not enough room in the C.T., a bearing plate with open sights and 6-power binoculars would be added to the C.T.. At the same time, all directors were to be fitted with receivers and, "as far as possible", ships were to have fore top, G.C.T. and controlling turrets fitted to transmit as well as receive, though this was noted as being impossible in some earlier ships.[24]

Mechanical Aid-to-Spotter

At some point, the ships in this class were equipped with a pair of Mechanical Aid-to-Spotter Mark Is, one on each side of the foretop, keyed off the Evershed rack on the director. As the need for such gear was apparently first identified in early 1916, it seems likely that these installations were effected well after Jutland.[25]

In 1917, it was decided that these should have mechanical links from the director and pointers indicating the aloft Evershed's bearing.[26]

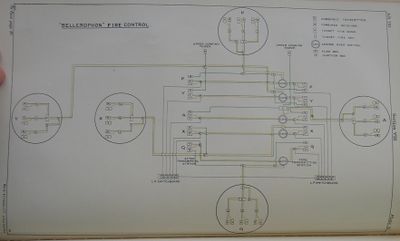

Gunnery Control

The control arrangements were as follows.[27]

Control Positions

- Fore top

- Main top

- "A" turret

- "Y" turret

Some ships had C.O.S.s within the control positions so they could be connected to either T.S..[28]

Control Groups

The five 12-in turrets were each a separate group with a local C.O.S. located in the forward T.S. so that it could be connected to:[29]

- Forward T.S.

- After T.S.

It seems likely that an additional C.O.S. within each turret permitted a choice between the T.S. selected in the C.O.S. above and local transmitters within own turret.[Inference]

Directors

Main Battery

The ships were completed without a director, but were eventually fitted with a geared tripod-type director in a light aloft tower on the foremast along with a directing gun in "Y" turret.[30] The battery was not divisible into groups for split director firing.[31]

The turret Elevation Receivers were Pattern H. 2, capable of 13.5 degrees elevation. The Training Receivers were the single dial type, pattern number 7.[32]

Secondary Battery

The 4-in guns never had directors installed.[33]

Torpedo Control

By the end of 1917, common torpedo control additions to all capital ships were to be adopted where not already in place. Those for Dreadnought and later classes with 18-in tubes were to include:[34]

- duplication of firing circuits and order and gyro angle instruments to allow all tubes to be directed from either C.T. or T.C.T.

- navyphones from both control positions to all tube positions

- bearing instruments between "control position, and R.F., and course and speed of enemy instruments where applicable, between the transmitting stations and the control positions."

- range circuits between R.F.s and control positions

Transmitting Stations

Like all large British ships of the era prior to King George V and Queen Mary, these ships had 2 T.S.es.[35]

Dreyer Table

Each ship was eventually retro-fitted with a Mark I Dreyer table, but was never given Dreyer Turret Control Tables.[36]

Fire Control Instruments

By 1909, all three ships were equipped with Barr and Stroud Mark II* Fire Control Instruments for range, deflection and orders.[38]

The Handbook for Fire Control Instruments, 1909 lists the Barr and Stroud Mark II* equipment on this class as:[39]

- Combined Range, Order, Deflection: 10 transmitters, 27 receivers

- Group Switches: 5

- Rate: 4 transmitters, 16 receivers

- Bearing: none

- Range: none

Additionally, this class had the following fire control equipment:[40]

- Siemens turret fire gongs: 10 with pushes in lamp boxes

- Fire Gongs: none

- Graham's Captain's Cease Fire Bells: 15 with 1 key

The ships also had Target Visible and Gun Ready signals, with indications of which turret could see the target and which guns were ready being visible in the TSes and control positions.[41]

In 1911, it was decided that the three ships should be fitted with "range, buzzer and bearing instruments for communication between control positions, control turrets and transmitting and plotting stations."[42]

Alterations

Telescopes

In September 1914, the ships were each to be sent eight 3/9 power telescopes and to return the same number of 2.5 power scopes, Pattern G. 329 upon receipt. These were likely to serve as trainer telescopes. Constrained supplies meant that 26% of the scopes actually supplied her may have wound up being 5/12 or 5/21 scopes.[43]

Instruments

In 1916, it was approved that the ships should have fire control instruments fitted for their 4-in armament. What precisely this means is unclear, but perhaps they did not previously have range and deflection receivers?[44]

See Also

Footnotes

- ↑ Burt. British Battleships of World War One. p. 66.

- ↑ Burt. British Battleships of World War One. p. 64.

- ↑ Admiralty Weekly Order No. 331 of 8 Sep, 1914.

- ↑ Annual Report of the Torpedo School, 1908. Wireless Appendix, p. 13.

- ↑ Admiralty Weekly Orders. 28 Feb, 1913. The National Archives. ADM 182/4.

- ↑ The Sight Manual. 1916. 4, 39, 106, 108-109.

- ↑ I am inferring this is the same as the B. VIII mounting)

- ↑ I am not sure why this would be.

- ↑ Brooks. Dreadnought Gunnery. pp. 45-46.

- ↑ Burt. British Battleships of World War One. p. 62.

- ↑ The Sight Manual. 1916. pp. 89-90, 108, Plate 39.

- ↑ Admiralty Weekly Orders. The National Archives. ADM 182/4. 21 Feb, 1913.

- ↑ Admiralty Weekly Order No. 470 of 22 Aug, 1913.

- ↑ Burt. British Battleships of World War One. p. 62.

- ↑ Grand Fleet Gunnery and Torpedo Orders. No. 167, part 5.

- ↑ Torpedo Manual, Vol. III, 1909. p. 265.

- ↑ Annual Report of the Torpedo School, 1909. pp. 13-4.

- ↑ Annual Report of the Torpedo School, 1913. p. 8.

- ↑ Admiralty Weekly Order No. 207 of 31 July 1914.

- ↑ Burt. British Battleships of World War One. p. 64.

- ↑ Annual Report of the Torpedo School, 1917. p. 198. (C.I.O. 481/17).

- ↑ conspicuously not named in sections in Handbook for Fire Control Instruments, 1914, pp. 33-9.

- ↑ Handbook for Fire Control Instruments, 1914. pp. 34-5.

- ↑ Annual Report of the Torpedo School, 1917. p. 230.

- ↑ The Technical History and Index, Vol. 3, Part 23. pp. 25-6.

- ↑ Annual Report of the Torpedo School, 1917. p. 230.

- ↑ Handbook for Fire Control Instruments, 1914. p. 7.

- ↑ Handbook for Fire Control Instruments, 1914. p. 7.

- ↑ Annual Report of the Torpedo School, 1908. Plate 31.

- ↑ The Director Firing Handbook. pp. 88, 142.

- ↑ The Director Firing Handbook. p. 88.

- ↑ The Director Firing Handbook. pp. 144, 146.

- ↑ The Director Firing Handbook. absent from list on p. 143.

- ↑ Annual Report of the Torpedo School, 1917. p. 209. (C.I.O. 4212/17.).

- ↑ Handbook for Fire Control Instruments, 1914. pp. 6-7.

- ↑ Handbook of Captain F. C. Dreyer's Fire Control Tables, 1918. p. 3.

- ↑ Annual Report of the Torpedo School, 1908. Plate 31.

- ↑ Handbook for Fire Control Instruments, 1909. p. 56.

- ↑ Handbook for Fire Control Instruments, 1909. p. 58.

- ↑ Handbook for Fire Control Instruments, 1909. p. 58.

- ↑ Handbook for Fire Control Instruments, 1914. p. 11.

- ↑ Annual Report of the Torpedo School, 1911. p. 95.

- ↑ Admiralty Weekly Order No. 408 of 25 Sep, 1914.

- ↑ Annual Report of the Torpedo School, 1916. p. 145.

Bibliography

- H.M.S. Vernon. Annual Report of the Torpedo School, 1911, with Appendix (Wireless Telegraphy). Copy 15 at The National Archives. ADM 189/31.

- Admiralty, Technical History Section (1919). The Technical History and Index: Fire Control in H.M. Ships. Vol. 3, Part 23. C.B. 1515 (23) now O.U. 6171/14. At The National Archives. ADM 275/19.

- Admiralty, Gunnery Branch (1917). The Director Firing Handbook. O.U. 6125 (late C.B. 1259). Copy No. 322 at The National Archives. ADM 186/227.

- Admiralty, Gunnery Branch (1918). Handbook of Captain F. C. Dreyer's Fire Control Tables, 1918. C.B. 1456. Copy No. 10 at Admiralty Library, Portsmouth, United Kingdom.

- Sumida, Jon Tetsuro (1989). In Defence of Naval Supremacy: Finance, Technology and British Naval Policy, 1889-1914. Winchester, Mass.: Unwin Hyman, Inc.. ISBN 0044451040. (on Amazon.com and Amazon.co.uk).

- Brooks, John (2005). Dreadnought Gunnery and the Battle of Jutland: The Question of Fire Control. Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 0714657026. (on Amazon.com and Amazon.co.uk).

- Admiralty (1920). Battle of Jutland 30th May to 1st June 1916: Official Despatches with Appendices. Cmd. 1068. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office.

| Bellerophon Class Dreadnought | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bellerophon | Superb | Temeraire | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| <– | H.M.S. Dreadnought | Battleships (UK) | St. Vincent Class | –> | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||