Difference between revisions of "Rosslyn Erskine Wemyss, First Baron Wester Wemyss"

Simon Harley (talk | contribs) (Oops.) |

Simon Harley (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

At the examination for Naval Cadetships, Wemyss placed eighteenth out of the successful batch of forty-six candidates.<ref>"Naval Cadetships" (News). ''The Times''. Saturday, 30 June, 1877. Issue '''28982''', col A, pg. 14.</ref> | At the examination for Naval Cadetships, Wemyss placed eighteenth out of the successful batch of forty-six candidates.<ref>"Naval Cadetships" (News). ''The Times''. Saturday, 30 June, 1877. Issue '''28982''', col A, pg. 14.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Wemyss was promoted to the rank of {{CommRN}} on 31 August, 1898.<ref>''London Gazette'': [http://www.london-gazette.co.uk/issues/27004/pages/5431 no. 27004. p. 5431.] 13 September, 1898.</ref> | ||

==Captain== | ==Captain== | ||

Revision as of 18:32, 21 March 2011

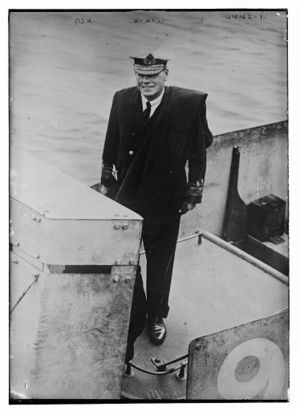

Admiral of the Fleet Rosslyn Erskine Wemyss, First Baron Wester Wemyss, K.C.B., C.M.G., Royal Navy (12 April, 1864 – 24 May, 1933) was an officer of the Royal Navy. He is chiefly remembered for his service in the Dardanelles Campaign during the First World War, followed by his elevation to the position of First Sea Lord in 1917.

Early Life & Career

Wemyss (pronounced "Weemz") was born in London on 12 April, 1864, the youngest and posthumous son of James Hay Erskine Wemyss, of Wemyss Castle, Fife, by his wife, Millicent Ann Mary, daughter of Lady Augusta Kennedy Erskine, the fourth daughter of the Duke of Clarence (later King William IV) by Mrs. Dorothy Jordan. His paternal grandfather, Rear-Admiral James Erskine Wemyss, was great-great-grandson of David, Third Earl of Wemyss, Vice-Admiral of Scotland, and his maternal great-grandfather, King William IV, had been the last holder of the office of Lord High Admiral of the United Kingdom.

At the examination for Naval Cadetships, Wemyss placed eighteenth out of the successful batch of forty-six candidates.[1]

Wemyss was promoted to the rank of Commander on 31 August, 1898.[2]

Captain

After two years at Osborne Wemyss was glad to return to the sea as captain of the Suffolk in the Mediterranean where Beresford was then commander-in-chief. He paid her off in April 1908 and, after a few months command of the Albion, flagship in the Atlantic Fleet, next year was appointed Commodore, Second Class, of the Royal Naval Barracks at Devonport, succeeding Commodore Arthur Yerbury Moggridge on 20 August, 1909.[3]

Wemyss's service there was interrupted for several months in 1910 while he commanded the Balmoral Castle which was commissioned to take the Duke and Duchess of Connaught to South Africa for the opening of the first Union parliament. He had accepted the offer of this command in April when the Prince of Wales had intended to undertake the ceremony, but the death of King Edward VII necessitated a change. King George made him extra naval equerry after his accession and he was appointed C.M.G. after the voyage.

Flag Rank

Wemyss was promoted to the rank of Rear-Admiral on 19 April, 1911.[4] He was relieved as Commodore at Plymouth by John de M. Hutchison on 25 April.[5] After his promotion, he apparently went to see the Second Sea Lord, Admiral Francis C. B. Bridgeman, who offered him command of the Mediterranean Cruiser Squadron (then the Sixth Cruiser Squadron) when it fell vacant, even though it entailed eighteen months on half-pay. Wemyss considered the appointment worth the wait and accepted it.[6] This story is somewhat suspect. The men ultimately responsible for appointments would have been either the Private Secretary to the First Lord of the Admiralty (Rear-Admiral E. C. T. Troubridge) or the First Lord himself. Seeing the First Sea Lord, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Arthur Wilson, would be more likely than seeing the Second Sea Lord.

His future supposedly settled, Wemyss and his family stayed in London, travelled to Wemyss, Vosges, and Cannes.[6] From 11 September to 22 December, 1911, he attended the War Course College.[7] There he came first in order of merit out of six flag officers who took part, and was described to have a "strong personalty & has [a] strong grasp of [the] strategical situation."[8]

It is asserted by Wemyss's wife that the new First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, had decided to give command of the Mediterranean Cruiser Squadron to Rear-Admiral Troubridge in order that he could appoint Rear-Admiral David Beatty as his Naval Secretary. In light of what Lady Wester Wemyss considered "so flagrant a breach of faith", Wemyss apparently sent in his resignation on 22 July, 1912, and was only dissuaded after a stormy interview with Churchill and by the promise of the next available seagoing appointment.[9]

The facts tell a very different story. Churchill had been appointed First Lord in October, 1911. Rear-Admiral Troubridge received the important new appointment of Chief of the Admiralty War Staff on 8 January, 1912, and was then replaced as Naval Secretary by Rear-Admiral Beatty. The command of the Mediterranean Cruiser Squadron, then the Sixth Cruiser Squadron, did not fall vacant until 3 June, when Rear-Admiral Sir Douglas A. Gamble hauled down his flag at Portsmouth. The command of the cruisers was taken over by the new Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean, Admiral Sir Berkeley Milne. The appointment of Troubridge in command of the Mediterranean Cruiser Squadron was not announced until late November.

Troubridge didn't take up his new command until 6 January, 1913, by which time Wemyss had already been at sea for over two months. For on 29 October, 1912 he was appointed Rear-Admiral Second-in-Command in the Second Battle Squadron in succession to Rear-Admiral Hugh Evan-Thomas.

Great War

Wemyss arrived back in London on 31 July, and visited the Admiralty, where he ascertained that he was to be given command of the Twelfth Cruiser Squadron. The mobilisation order went out on Saturday, and Wemyss, accompanied by his wife and his Flag Lieutenant, Bevan, headed to Plymouth. He hoisted his flag in the cruiser Charybdis on 2 August.[10]

His orders were to act in concert with the French Admiral Rouyer in charge of the western patrol in the English Channel for the protection of the transports conveying the British Expeditionary Force to France. Constantly at sea in an old uncomfortable ship without any sign of the enemy, Wemyss found this a tiresome task, and was glad when in September his squadron was sent to Canada to escort the first contingent of 30,000 Canadians to England. This duty was successfully accomplished, although Wemyss himself considered that old slow cruisers were a risky protection to a convoy. He then resumed charge of the western patrol, transferring his flag to the Euryalus until February 1915, when he hauled it down on the dispersal of his cruiser force.

Wemyss was at once selected for a new duty as governor of the island of Lemnos and to take charge of a naval base to be created at Mudros for the impending naval and military Dardanelles campaign, although occupying a most anomalous position in foreign territory without staff or detailed orders to guide him. He was required to organize and equip a base for a great army and fleet on an island which had no facilities for landing troops or discharging cargo, no water supply, and no native labour. He set to work at once with great energy and resourcefulness and in a few weeks troops were able to land and assemble for the attack on the Gallipoli peninsula. In March Vice-Admiral Sir Sackville H. Carden, the commander-in-chief, had to give up the command through ill health. His second-in-command, Rear-Admiral Sir John M. De Robeck, was junior to Wemyss, although older, but Wemyss with great public spirit himself proposed that De Robeck should succeed Carden with the acting rank of vice-admiral, remaining himself in charge of Mudros.

In April Wemyss was able to take an active part in the landing operations in command of the first naval squadron, being in charge of the Helles section, with his flag in his former flagship Euryalus, and having Lieutenant-General Sir Aylmer Hunter-Weston and his staff on board. Throughout this critical and dangerous work he maintained close co-operation with the military authorities, readily accepted ideas from his own officers, such as the celebrated beaching of the cargo ship River Clyde, and helped to maintain the morale of the whole expedition by his indomitable cheerfulness and imperturbability. In August he was mentioned in dispatches for his invaluable services in the Gallipoli landing.

On 1 January, 1916, he was appointed a Knight Commander of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath (K.C.B.).[11] The Euryalus was again his flagship and he soon found opportunities of effective co-operation with the military commanders in the defence of Egypt against the Turks and the Senussi rising and in the support of General Sir Archibald Murray's advance to Sinai. He then took his squadron to the Persian Gulf and went himself up the Tigris in a river-gunboat to try to relieve the critical situation in Mesopotamia. In a forlorn hope of saving the garrison of Major-General Sir C. V. F. Townshend [q.v.] at Kut from surrender he attempted to get a food ship through to the town; it failed, but he could not rightly refuse the military appeal for help. He then completed his tour of his station, visiting both India, where he saw the viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, and Ceylon, and, after meeting Rear-Admiral (Sir) W. L. Grant, commander-in-chief, China station, at Penang, he returned to Egypt in August in time to support the advance by General Sir Edmund Allenby [q.v.] into Palestine, and foster the Arab revolt by his patrols in the Red Sea. He established cordial relations with the Emir Feisal and T. E. Lawrence, as well as with the generals. He was confirmed in the rank of Vice-Admiral on 6 December, vice Warrender.[12]

Allegedly, Wemyss told his successor as Commander-in-Chief, East Indies, Vice-Admiral Gaunt, "to look out for two troublemakers, a little pipsqueak called Lawrence in Arabia, and a tiresome nigger by the name of Gandhi."[13]

In June 1917 under an agreement between Great Britain, France, and Italy it was decided to appoint a vice-admiral as commander-in-chief of the British ships in the Mediterranean with headquarters at Malta. Wemyss was offered and accepted the appointment, but on returning to London for instructions he was invited by Sir Eric Geddes [q.v.] , who had just succeeded Sir Edward Carson [q.v.] as first lord, to join his Board as second sea lord; that official had hitherto been expected to take the place of the first sea lord in his absence. But on further reflection Geddes decided to leave the second sea lord to carry on his personnel work and in September created a new office of deputy sea lord for Wemyss.

First Sea Lord

About Wemyss's suitability for the position of First Sea Lord, Lord Fisher was asked by George E. Buckle, lately editor of The Times, "BUT HAS HE BRAINS??" Fisher recounted, "I gave Buckle an evasive answer! I replied, "He has tact!"[14]

Resignation & Retirement

Wemyss was confirmed in the rank of Admiral on 21 February, 1919.[15] At home Wemyss took a leading part in securing substantial increases in the remuneration of the naval service. His new chief in Whitehall was Walter Long [q.v.] , and, much hurt by an anonymous press agitation demanding his replacement by Sir David Beatty and by his exclusion in July from the list of peerages and money awards to the principal war leaders, in that month he asked his leave to resign. Long refused, but a few months later feeling himself out of sympathy with the government's attitude to the revolutionary Russian régime and to the maintenance of this country's naval supremacy, Wemyss decided definitely to resign and left office on 1 November 1919, being specially promoted Admiral of the Fleet on 29 December, dated 1 November.[16] He was raised to the Peerage of the United Kingdom as Baron Wester Wemyss of Wemyss in the County of Fife on 20 November,[17] resurrecting the title of an ancient Scottish barony in his family. He remained on half pay until he reached the age limit and retired in 1929, having received no further government employment as a governor or ambassador which he felt he had a right to expect, and lived mainly at Wemyss and at Cannes. But he was actively engaged as director of the Cables and Wireless Company and the British Oil Development Company, conducting a successful mission on behalf of the latter to the Middle East in 1927 and to South America on behalf of the former in 1929. He maintained his intense interest in foreign affairs and occasionally expressed his views in the House of Lords and in the press, particularly his hostility to the Turkish treaty of 1920, and to the Washington naval treaty of 1922.

Wester Wemyss married in 1903 Victoria, the only daughter of Sir Robert Burnett David Morier [q.v.] , the eminent diplomat, and had one daughter. He died at Cannes 24 May 1933 and was buried in the chapel garden of Wemyss Castle after preliminary services at Cannes and Westminster Abbey, at which naval honours were officially accorded to him.

There is a drawing of Wester Wemyss by Francis Dodd in the Imperial War Museum, and his portrait is included in Sir A. S. Cope's picture "Some Sea Officers of the Great War," painted in 1921, in the National Portrait Gallery.

Footnotes

- ↑ "Naval Cadetships" (News). The Times. Saturday, 30 June, 1877. Issue 28982, col A, pg. 14.

- ↑ London Gazette: no. 27004. p. 5431. 13 September, 1898.

- ↑ Hazell's Annual, 1910. p. 199.

- ↑ London Gazette: no. 28487. p. 3093. 21 April, 1911.

- ↑ "Naval and Military Intelligence" (Official Appointments and Notices). The Times. Friday, 21 April, 1911. Issue 39565, col G, pg. 4.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Wester Wemyss. Life and Letters. p. 128.

- ↑ Wemyss Service Record. The National Archives. ADM 196/42. p. 223.

- ↑ The National Archives. ADM 203/99. p. 47.

- ↑ Wester Wemyss. Life and letters. pp. 131-132.

- ↑ Wester Wemyss. Life and Letters. pp. 157-159.

- ↑ London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 29423. p. 79. 31 December, 1915.

- ↑ London Gazette: no. 29853. p. 11970. 8 December, 1916.

- ↑ Sheila de Moleyns. Tape recording in possession of the Liddle Collection, University of Leeds.

- ↑ Fear God and Dread Nought. III. p. 497.

- ↑ London Gazette: no. 31223. p. 3294. 11 March, 1919.

- ↑ London Gazette: no. 31715. p. 57. 2 January, 1920.

- ↑ London Gazette: no. 31651. p. 14036. 21 November, 1919.

Bibliography

- "Lord Wester Wemyss" (Obituaries). The Times. Thursday, 25 May, 1933. Issue 46453, col B, pg. 18.

- "Lord Wester Wemyss: French Tributes at Funeral Service" (Obituaries). The Times. Monday, 29 May, 1933. Issue 46456, col D, pg. 13.

- "Lord Wester Wemyss: Official Arrangements for Funeral" (Obituaries). The Times. Tuesday, 30 May, 1933. Issue 46457, col D, pg. 18.

- "Lord Wester Wemyss: Appreciations" (Obituaries). The Times. Tuesday, 30 May, 1933. Issue 46457, col C, pg. 21.

- "Lord Wester Wemyss: Funeral Service at the Abbey" (Obituaries). The Times. Wednesday, 31 May, 1933. Issue 46458, col C, pg. 19.

- Wester Wemyss, Admiral of the Fleet Lord, G.C.B. (1924). The Navy in the Dardanelles Campaign. London: Hodder and Stoughton Limited.

- Wester Wemyss, Lady (1935). The Life and Letters of Lord Wester Wemyss. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode.

Papers

Service Records

- The National Archives. ADM 196/42.

- The National Archives. ADM 196/20.

| Naval Offices | ||

| Preceded by Herbert G. King-Hall |

Rear-Admiral in the Second Battle Squadron 1912 - 1913 |

Succeeded by Sir Robert K. Arbuthnot, Bart. |

| Preceded by New Command |

Rear-Admiral Commanding, Twelfth Cruiser Squadron 1914 - 1915 |

Succeeded by Command Abolished |

| Preceded by Sir Richard H. Peirse |

Commander-in-Chief on the East Indies Station 1916 - 1917 |

Succeeded by Ernest F. A. Gaunt |

| Preceded by Sir Cecil Burney |

Second Sea Lord 1917 |

Succeeded by Sir Herbert L. Heath |

| Preceded by New Position |

Deputy First Sea Lord 1917 |

Succeeded by George P. W. Hope |

| Preceded by Sir John R. Jellicoe |

First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff 1917 – 1919 |

Succeeded by Sir David Beatty |

- 1864 births

- 1933 deaths

- Personalities

- H.M.S. Britannia (Training Ship) Entrants of July, 1877

- Commanding Officers of the Royal Naval College, Osborne

- Commanding Officers of H.M.S. Suffolk 91903)

- Commanding Officers of H.M.S. Albion (1898)

- Commodores, Devonport Royal Naval Barracks

- Commanding Officers of H.M.S. Balmoral Castle (1910)

- Rear-Admirals in the Second Battle Squadron (Royal Navy)

- Rear-Admirals Commanding, Cruiser Force G (Royal Navy)

- Senior Naval Officers, Mudros

- Commanders-in-Chief on the East Indies Station

- Second Sea Lords

- Deputy First Sea Lords

- First Sea Lords

- Royal Navy Admirals of the Fleet

- Royal Navy Flag Officers